|

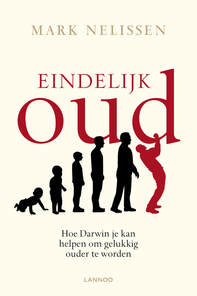

Finally, I’m old!

What Darwin can tell us about the usefulness and beauty of growing older Mark Nelissen 256 pp. – 100,000 words LANNOO Kasteelstraat 97 | B-8700 Tielt | Belgium | t +32-51424211 | www.lannoo.com For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected] or [email protected] |

‘You gave me peace of mind!’ Behavioural biologist Mark Nelissen had countless people tell him that they felt happier after reading his books on the Darwinian view on life. The realisation that our day-to-day behaviour is influenced by our evolutionary past and that there’s a logical explanation for so many things in our life, is not only very clarifying, it also entails a certain peace of mind.

For the first time, Mark Nelissen’s latest book zooms in on a theme that’s always on everyone’s minds: growing old. It strives not only to assuage his (older) readers, but also to restore the elderly to their rightful place in modern-day society, which seems to conduct itself with the motto ‘forever young’.

Growing old is scary and many elderly people are often side-lined and considered ‘no longer useful’. Behavioural biologist Mark Nelissen proves that the opposite is true. Grandmas and grandpas are there because old age has an evolutionary use. Even better: the existence of human kind is deeply intertwined with the existence of old age. In Finally Old, Mark Nelissen makes a case for those of us who are over fifty. He clearly explains the origin of old age from an evolutionary point of view, the biological meaning of growing old, the purpose of the menopause and, most importantly, why we should be looking forward to… finally growing old.

For the first time, Mark Nelissen’s latest book zooms in on a theme that’s always on everyone’s minds: growing old. It strives not only to assuage his (older) readers, but also to restore the elderly to their rightful place in modern-day society, which seems to conduct itself with the motto ‘forever young’.

Growing old is scary and many elderly people are often side-lined and considered ‘no longer useful’. Behavioural biologist Mark Nelissen proves that the opposite is true. Grandmas and grandpas are there because old age has an evolutionary use. Even better: the existence of human kind is deeply intertwined with the existence of old age. In Finally Old, Mark Nelissen makes a case for those of us who are over fifty. He clearly explains the origin of old age from an evolutionary point of view, the biological meaning of growing old, the purpose of the menopause and, most importantly, why we should be looking forward to… finally growing old.

The strength and unicity of this book

1. ‘Finally, I’m Old’ is the first book to look at the topic of old age from a Darwinian perspective

Every hominid ancestor that preceded us on our evolutionary path died before the age of forty. ‘Finally, I’m Old’ explains how people only started living longer lives about forty thousand years ago. Their life spans doubled around that time. That drastic life span increase brought along big changes: culture had remained fairly primitive up to that point, but from then on, it boomed and rose to new heights. The art from that period can rival our contemporary artists. Society grew much more complex. Later, agriculture, cities and religions would come into existence. All of this was made possible by old age. From that time onwards, humans were the only species with two functional phases of life: a first phase which focused primarily on procreation, and a second one which strived to improve culture, politics and societal organisation.

The classic perspective states that only the first phase of life, youth, is beautiful, and that old age is unnecessary and the elderly should be side-lined. This book’s evolutionary view on humanity proves that that perspective is flawed. Take the menopause, for example. People used to think that it was a process that made a woman lose much of her dignity, since she had lost her ability to procreate. However, biological analysis have shown that the menopause has proven to be a highly important phase for human kind as a whole. Grandmothers contribute to the protection and upbringing of their grandchildren, giving them a much better chance at survival, especially in our collective past. There are even more clues that attest to the importance of old age. The second life phase brings men and women more wisdom, peace of mind, creativity and many more precious things that make humanity great. The widespread culture of asking the elders of a community for advice, seems to have become a thing of the past in modern society, but it should be restored. Even if Google seems to have the answers to every question.

2. ‘Finally, I’m Old’ separates myth from truth

Growing old is a complicated process that’s being scrutinised extensively by researchers, who hope to find the holy grail of aging. The dream of a means to keep people young, or at least limit the discomfort of old age. And in fact, just about every senior citizen has the same dream. ‘Finally, I’m Old’ separates myth from truth and provides scientifically substantiated advice to lessen the negative effects of growing old, while enhancing the positive.

A good example of such advice is the importance of social activities. Throughout history, human kind has built social networks to increase their chance of survival, but even today, friendships and a large social network have a surprising impact. For example, friendship can help to improve an older person’s health. And against all odds, Facebook can help, as well.

The book deals with several other questions, as well. Why does time seem to pass so much faster than it used to? Can you slow it down? And can you prolong your life? Is it true that older people are happier than their younger peers? And can you increase your happiness?

3. ‘Finally, I’m Old’ has a positive outlook on the future

Where are we going? How will people experience aging in the future? What are older people’s prospects for tomorrow? The good news is that it looks good. ‘Finally, I’m Old’ describes the wonderful techniques that are still being developed today, which can be used to make the life of the elderly easier in the future. Both in terms of medicine and social life, the future holds developments that will make old age even more comfortable than today. For example, their housing arrangements will be better adjusted and they will receive better care in retirement homes.

4. ‘Finally, I’m Old’ renders the science accessible to the larger audience

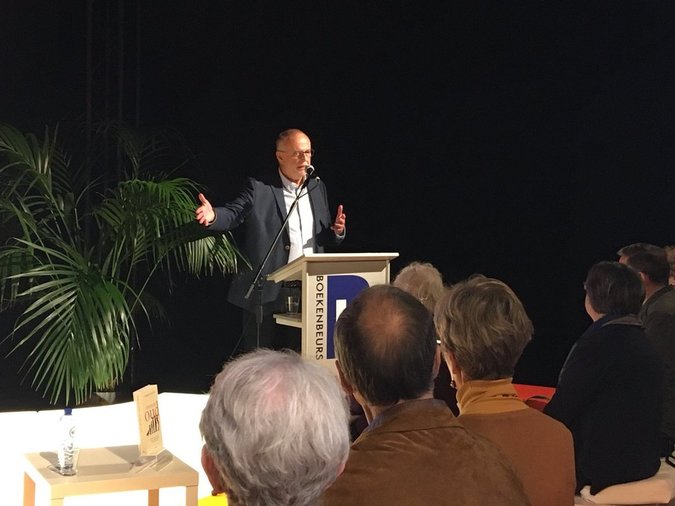

Professor Mark Nelissen was described by an authoritative scientific journal as the Flemish answer to Richard Dawkins, Oliver Sack and Steven Pinker. Like no other, he knows how to use his good sense of humour to translate the science for the laymen audience.

1. ‘Finally, I’m Old’ is the first book to look at the topic of old age from a Darwinian perspective

Every hominid ancestor that preceded us on our evolutionary path died before the age of forty. ‘Finally, I’m Old’ explains how people only started living longer lives about forty thousand years ago. Their life spans doubled around that time. That drastic life span increase brought along big changes: culture had remained fairly primitive up to that point, but from then on, it boomed and rose to new heights. The art from that period can rival our contemporary artists. Society grew much more complex. Later, agriculture, cities and religions would come into existence. All of this was made possible by old age. From that time onwards, humans were the only species with two functional phases of life: a first phase which focused primarily on procreation, and a second one which strived to improve culture, politics and societal organisation.

The classic perspective states that only the first phase of life, youth, is beautiful, and that old age is unnecessary and the elderly should be side-lined. This book’s evolutionary view on humanity proves that that perspective is flawed. Take the menopause, for example. People used to think that it was a process that made a woman lose much of her dignity, since she had lost her ability to procreate. However, biological analysis have shown that the menopause has proven to be a highly important phase for human kind as a whole. Grandmothers contribute to the protection and upbringing of their grandchildren, giving them a much better chance at survival, especially in our collective past. There are even more clues that attest to the importance of old age. The second life phase brings men and women more wisdom, peace of mind, creativity and many more precious things that make humanity great. The widespread culture of asking the elders of a community for advice, seems to have become a thing of the past in modern society, but it should be restored. Even if Google seems to have the answers to every question.

2. ‘Finally, I’m Old’ separates myth from truth

Growing old is a complicated process that’s being scrutinised extensively by researchers, who hope to find the holy grail of aging. The dream of a means to keep people young, or at least limit the discomfort of old age. And in fact, just about every senior citizen has the same dream. ‘Finally, I’m Old’ separates myth from truth and provides scientifically substantiated advice to lessen the negative effects of growing old, while enhancing the positive.

A good example of such advice is the importance of social activities. Throughout history, human kind has built social networks to increase their chance of survival, but even today, friendships and a large social network have a surprising impact. For example, friendship can help to improve an older person’s health. And against all odds, Facebook can help, as well.

The book deals with several other questions, as well. Why does time seem to pass so much faster than it used to? Can you slow it down? And can you prolong your life? Is it true that older people are happier than their younger peers? And can you increase your happiness?

3. ‘Finally, I’m Old’ has a positive outlook on the future

Where are we going? How will people experience aging in the future? What are older people’s prospects for tomorrow? The good news is that it looks good. ‘Finally, I’m Old’ describes the wonderful techniques that are still being developed today, which can be used to make the life of the elderly easier in the future. Both in terms of medicine and social life, the future holds developments that will make old age even more comfortable than today. For example, their housing arrangements will be better adjusted and they will receive better care in retirement homes.

4. ‘Finally, I’m Old’ renders the science accessible to the larger audience

Professor Mark Nelissen was described by an authoritative scientific journal as the Flemish answer to Richard Dawkins, Oliver Sack and Steven Pinker. Like no other, he knows how to use his good sense of humour to translate the science for the laymen audience.

Table of contents

Chapter 1. A warm message

For fall too long, we have looked upon ageing as something negative. In this introductory chapter, Mark Nelissen explains that looking at old age from a Darwinian perspective is a true eye-opener.

Chapter 2. A history of falling and getting back up again

How did human kind evolve from its ancestors? How did anthropoid apes gradually turn into hominids and eventually humans? How did our ancestors live? Did they know art? Politics? Did they, too, have grandpas and grandmas?

Chapter 3. Culture with ancient roots

Suddenly, a few tens of thousands of years ago, the elderly came into existence. The various types of intelligence merged into one super computer. Women developed their menopause. Human life was split into two phases, resulting in more creativity, a richer culture and the start of our technological advancement.

Chapter 4. Growing old, how does one do that?

What is the purpose of the menopause? Which status did the elderly have in the early tribes of hunters and gatherers? We explore the true meaning of growing old. How are chromosomes involved, and what about certain molecules, food and hormones? Is it possible to extend our lives even further? How old can we really grow?

Chapter 5. The colours of phase two

Older people have a different social life from young people. They’re also wiser, although that is often neglected.

Chapter 6. Staying young and prolonging your life, is that possible?

There are several techniques you can use to prolong your life. We focus on the ones that are based on the power of social activities, taking care of others, physical exercise and remaining active. The right diet also has an impact. What can we do?

Chapter 7. Never too old for sex

We explore the essence of sex and ask ourselves whether it should be linked to our younger years. Do older people still have sex? Of course, and more often than not, they even enjoy it more than their younger peers. What is a beautiful body, and does old equal ugly?

Chapter 8. In search of happiness

We define happiness and look for ways to increase ours at the end of our lives, amongst other things, by taking away fear. Does life have meaning? And do we need money to be happy?

Chapter 9. The final sunset

We shouldn’t be afraid to discuss the end of life and impending death in this book. Why does time seem to pass faster than it used to? Can we slow it down? Is there a life after death? We describe some near-death experiences and draw lessons from them. And finally, we discuss the end of life.

Chapter 10 Where are we going?

What could the life of older people look like in the near future? They will live differently, have more money and better medical assistance at their disposal, they will be more and more assisted by computing technology, etc.

For fall too long, we have looked upon ageing as something negative. In this introductory chapter, Mark Nelissen explains that looking at old age from a Darwinian perspective is a true eye-opener.

Chapter 2. A history of falling and getting back up again

How did human kind evolve from its ancestors? How did anthropoid apes gradually turn into hominids and eventually humans? How did our ancestors live? Did they know art? Politics? Did they, too, have grandpas and grandmas?

Chapter 3. Culture with ancient roots

Suddenly, a few tens of thousands of years ago, the elderly came into existence. The various types of intelligence merged into one super computer. Women developed their menopause. Human life was split into two phases, resulting in more creativity, a richer culture and the start of our technological advancement.

Chapter 4. Growing old, how does one do that?

What is the purpose of the menopause? Which status did the elderly have in the early tribes of hunters and gatherers? We explore the true meaning of growing old. How are chromosomes involved, and what about certain molecules, food and hormones? Is it possible to extend our lives even further? How old can we really grow?

Chapter 5. The colours of phase two

Older people have a different social life from young people. They’re also wiser, although that is often neglected.

Chapter 6. Staying young and prolonging your life, is that possible?

There are several techniques you can use to prolong your life. We focus on the ones that are based on the power of social activities, taking care of others, physical exercise and remaining active. The right diet also has an impact. What can we do?

Chapter 7. Never too old for sex

We explore the essence of sex and ask ourselves whether it should be linked to our younger years. Do older people still have sex? Of course, and more often than not, they even enjoy it more than their younger peers. What is a beautiful body, and does old equal ugly?

Chapter 8. In search of happiness

We define happiness and look for ways to increase ours at the end of our lives, amongst other things, by taking away fear. Does life have meaning? And do we need money to be happy?

Chapter 9. The final sunset

We shouldn’t be afraid to discuss the end of life and impending death in this book. Why does time seem to pass faster than it used to? Can we slow it down? Is there a life after death? We describe some near-death experiences and draw lessons from them. And finally, we discuss the end of life.

Chapter 10 Where are we going?

What could the life of older people look like in the near future? They will live differently, have more money and better medical assistance at their disposal, they will be more and more assisted by computing technology, etc.

Excerpt from Chapter 1. A warm message

The night had wrapped its blanket around Amsterdam. It was spoiled by the drizzling rain. Wet gusts of wind lashed onto the windows. Inside, the cosy warmth of the hall held me prisoner. I didn’t want to leave, although my lecture had been finished. The audience was fascinated and the inviting association’s president had been forced to interrupt their endless flow of questions. Otherwise, we would have kept going until morning. The people who attended, left the lecture hall in vigorous conversation. The secretary and his wife were busy moving chairs, but I wasn’t ready to face the drizzle yet. I took longer than I needed to disconnect my laptop and the accompanying apparel. Excruciatingly slowly, my notes disappeared into my briefcase and I patiently coiled up the cable of my beamer with the utmost precision. I drank the last bit of water in my glass as if it were an expensive glass of whisky. I usually move with much more spring in my step, but that night I let the fatigue and my aversion to the unpleasant weather get the best me. The window blinds were pulled up so I could see the rain drizzling down in the gleam of a street light. It would be a long drive back to Antwerp. And it wouldn’t get any shorter if I kept delaying my departure, but I didn’t feel like rushing home.

Like always after a lecture, I felt pleasantly tired and content. I wasn’t just cherishing the warmth of the lecture hall, but also the audience’s fascination. The series of questions I got after my lecture, showed that they had been wildly interested in what I had to say. After all, it was probably a new topic for most of the audience: ‘A new view of humanity through Darwinism.’ I got yet another opportunity to tell Darwin’s story and change people’s perception of humanity. The audience understood that we gain insight in our origin from an evolution of many millions of years. I told them how our ancestors adapted to their surroundings for tens and hundreds of thousands of years. And how we inherited those adaptations and how that explains that we show behaviour that seems useless today, but was very useful a long time ago. I had posed a few surprising examples and the audience had responded with wide eyes and open mouths. I feel privileged whenever I get the chance to reach so many people. Their minds will still be with Darwin when they get home and they will ponder their encounter with Darwin’s remarkable views for quite some time.

This all happened a few years ago and, normally, I wouldn’t remember that night so clearly. It wasn’t all that different from all my other lectures. But I will remember it for the rest of my life. That night in Amsterdam has been carved into my memory as if it was my first and only time in front of an audience ever. The reason is that one simple sentence which was whispered to me at the end of the lecture.

Just like students in university, there are always some members of the audience who sneak up to me after the questions have been concluded, with a question of their own. They’re often embarrassed about their question, or afraid it will sound childish, politically incorrect or that it’s already been answered without them noticing… There were individuals like that on that night, as well, but even those had already left, when I was startled. Suddenly someone appeared in the corner of the hall, which had seemed abandoned by then. He came out of nowhere. Step by step he reluctantly approached me, cautiously floundered between the chairs, which were still waiting to be collected by the secretary or his wife. He looked over his shoulders to make sure he wasn’t followed and tried his best to avoid looking me in the eyes, as if he wanted to remain invisible to me, as well. He looked slightly older than me, so very old, and rather short. Then he whispered the sentence.

‘Uh, professor…’, he stammered, ‘ you have given me peace of mind.’ He didn’t look me in the eyes, but fixed his on my hands, as they scrupulously coiled up a cable. So he didn’t see the surprised expression on my face. I was paralysed, at a loss for words. Although the man has spoken quietly and timidly, his sentence echoed loudly in my head. ‘You have given me peace of mind!’ My brain came to a full stop, because this didn’t make sense. Perhaps this man confused me with another lecturer. A priest, maybe? Or a yoga instructor? Maybe he just came from a self-help group? Did he realise I was talking about biology, about human behaviour and evolution?

‘Uh…What do you mean?’ I stuttered clumsily. ‘How could a… scientific exposition… give anyone peace of mind?’ There was an awkward silence and we both realised we weren’t thinking on the same wavelength.

‘I have felt a certain inner calm come over me ever since I first read your first book, Darwin’s glasses. And your later publications only increased that feeling. And so did your lectures, of which I’ve seen a few.’ I still didn’t understand what he was on about. I’m not a guru, pastor or therapist. I’m a cold, rational scientist. When I apologetically told the old man about this objection, he still didn’t seem to understand what I was trying to say.

‘Yes, but your views and analyses take the fears away! You talk about our origin and evolution. You explain why we behave this way and not differently and you find those explanations in our history. I’ve gradually come to realise that we have inherited our traits and characteristics from our predecessors. That’s…I mean, isn’t that… amazing?’ And the grey in his face seemed to regain its colour. His voice grew enthusiastic.

‘Sir, I’m afraid I still don’t follow. I’m pleased to hear that you appreciated my books and that you were convinced by what I wrote. However, you spoke of fears being taken away. What does that have to do with Darwinism?’

‘Well,’ he replied, ‘I grew up with fear: you are constantly being watched by an invisible being that sees your every mistake, wherever you are. And sooner or later, you have to pay. If you do well, you will be rewarded, but that promise doesn’t take away your fear of being punished. This invisible force, well, it’s intangible, you can’t feel or hear it. You are supposed to talk it regularly, though, which means you have to pray. And if you fail to do that regularly, that counts as a mistake, as well. Others tell you what this supreme force wants, but you never hear its voice for yourself. No, I’ve known plenty of fear, I grew up with them. It’s guided my every move!’

The poor man paused for a minute, his back bent, as if he needed a moment to recover from his memories of the threat of hell and damnation. And then he looked at me, composed himself and continued.

‘However, Darwinism is a completely different story! Its explanations are always crystal clear – as you have said many times yourself – and they require no divine intervention. Things come into existence through natural processes. No more fears, no more invisible deities, no more ordained dogmata. You have no idea how enlightening that is, professor. And when I say enlightening, I mean it has both offered me knowledge and taken away my burden. And Darwin’s glasses was the first step.’

To be honest, I understood very well what he meant when he called Darwinism enlightening, because I experienced it myself. Not at his age – which I haven’t reached yet, by the way – but when I was a teenager, reluctantly learning about evolution and how it seemed to contradict my catholic upbringing. I was starting to understand the man, but I was a little shocked at how my words alone had turned his faith around. I wrote a mission statement on my website, my calling to share the beautiful story of evolution – and of human kind, in particular – with as many people as I can. I don’t have the right to keep that beauty to myself, I have to share it! But there is nothing about bringing people peace of mind, taking away their fear or offering them certainty. If that is one of the side effects of my writing, it would significantly increase my satisfaction when people read my books. I am harvesting more than I sowed. What a rich man I am!

The short man’s sentence about peace of mind doesn’t just help me remember that night in Amsterdam, but it’s also been the seed from which this book eventually grew. During the two seconds when he said ‘you have given me peace of mind’, this book’s embryonic seed was planted in my mind. That sentence was like a sperm cell fertilising one of the egg cells in my brain. I know there are no genitals in my brain, but there are ideas. Ripening and maturing like egg cells in an ovary. Just like egg cells are either lost or fertilised by a sperm cell, ideas also whither or grow through contact with another thought, a suggestion, an event or one simple sentence…

The conception has taken many years already and I feel the urge to say I’m pregnant with a baby elephant, but that’s not true. The embryo has gone dormant many times because I wrote other books. Other egg cells impregnated by a sperm cell demanded priority in womb of my brain. There’s no room for twins there. Only one idea at a time can grow to adulthood. And so the other embryos are silenced, encouraged to rest and wait for better times. Someday! Today is that someday for the peace-of-mind embryo. The book you are holding now, is the lovechild of two ideas: on the one hand there’s the Darwinist, evolutionary view and on the other hand there is the inner peace and joy you can feel from knowing and understanding.

In the meantime, my conversation with the short, old man in Amsterdam had only gotten more cosy, but we were rudely interrupted by the secretary who turned off the lights to signal us that we were kindly requested to vacate the premises. I shook the man’s hand whole-heartedly, told him goodbye and walked out into the drizzling rain. I wonder if the man knew he would become the father of a book.

This all sounds like this book was written in response to a single statement by a single man. Of course, that’s not true, it is much more than that. Since that night, I have paid attention to the connection between knowing and feeling and I’ve opened myself up to similar remarks. I noticed many people e-mailed me similar stories, people looking for stability who found it in scientific knowledge about ourselves. It became more and more apparent that the short old man from Amsterdam and I were not the only ones who found peace of mind by studying our history. Many more people shared our experiences!

And so, the urge to share this message with more people grew inside of me. A message that states that happiness can be found in knowledge, rather than in supernatural forces. Happiness, joy, peace of mind… Everyone wants that. Whether they be male or female, black or white, tall or short, young or old…every single one of us wants to live a happy life and we strive to achieve that every day. It’s a universal truth that applies to anyone anywhere, and at any time in our history. However, the road to happiness is not that easy to walk, or even find.

You can try to attain happiness through cake, gin, coke, Prozac, yoga or mindfulness, with the help of a deity or a guru and whatever else there is. However, and I hope you agree by the time you’ve finished the book, you can also try to know, to grasp as best as you can the knowledge of everything that exists, and of yourself particularly. To know where things come from, to understand why you act or feel a certain way, to grasp how things work, what the essence of a certain phenomenon is… They are all anchors that give you certainty. And not just certainty, either. They can also bring beauty into your life, as well as make you feel good and give you peace of mind. Scientific analyses might not be as riveting as a good thriller, but they can create things that are more beautiful and pure than any poem. They give you insight and help you to understand and to see the connections between things. And that can grow into the highest form of beauty.

About the author

Mark Nelissen is a professor emeritus in behavioural biology at the university of Antwerp. He taught Human Behaviour: behavioural biology and evolutionary psychology, biological anthropology, cellular biology and animal welfare. He is a member of, among others, the European Society of Human Ethology, the International Primatological Society, the Human Evolution and Behavior Network and the American Anthropological Association. He has made it his personal mission to spread the insights of Darwinism with as many people as he can. His book, Darwin in the supermarket, was published in Dutch, French, Spanish, Portuguese, Hungarian, Bulgarian, Korean and Chinese. Finally, I'm old! was published in Korean.

On the work of Mark Nelissen

‘Science needs talented interpreters. Great Britain has Richard Dawkins and Robert Wright, the States have Oliver Sack and Steven Pinker. Flanders has Mark Nelissen.’

EOS Magazine

‘Nelissen clearly elucidates why we need to know the modern theory of evolution to explain how people think and act.’

Professor Johan Braeckman, University of Ghent

‘Biologist Mark Nelissen considers it his mission to spread Darwinism with as many people as possible. And he does so splendidly again with his new book.’

Knack Magazine on ‘The Brain Machine’

‘Once you pick up this book, you won’t be able to put it back down. It’s compelling. I thoroughly enjoyed it!’

BNR News Radio Holland on ‘Darwin in the supermarket’

EOS Magazine

‘Nelissen clearly elucidates why we need to know the modern theory of evolution to explain how people think and act.’

Professor Johan Braeckman, University of Ghent

‘Biologist Mark Nelissen considers it his mission to spread Darwinism with as many people as possible. And he does so splendidly again with his new book.’

Knack Magazine on ‘The Brain Machine’

‘Once you pick up this book, you won’t be able to put it back down. It’s compelling. I thoroughly enjoyed it!’

BNR News Radio Holland on ‘Darwin in the supermarket’